Snapshots from the Seventies

anemoia

n. a nostalgia for a time we've never known. Derived from the Greek anemos, "wind" + noos "mind." It's a psychological corollary to anemosis, which is a condition in the wood of some trees in which the wood is warped and the rings are separated by the action of high winds upon the trunk. In anemoia, the sheer force of time warps something in your mind, until you find yourself beginning to bend backward, leaning into the wind.

— John Koenig, The Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows

I was around four or five when Mommy first told me about Dad. She said that they couldn't marry because he was already betrothed to someone else from birth, as is the custom among upper-class Indians. The exchange and merging of property was supposedly a done deal—there might have been some resort island involved, as a dowry. In the years that followed, the mental images that came to mind involved a mix of Bedouin tents, elephants, peacocks, turbans, all manner of exotic clichés my young imagination cobbled together from the Arabian Nights and the World Book Encyclopedia's volume on entries under the letter I.

The years came with more meeting and finding affinity with characters with relatively humble backgrounds and obscure but legendary fathers: Arthur Pendragon, Telemachus, Luke Skywalker. I wouldn't begin to find out the actual story until my dad first contacted me by email in May 2005, around ten years ago. A flurry of email exchanges took place between him in Bangalore, me here in Manila, and Mommy in Maryland. Somewhere in that exchange, Mommy sent me this photo:

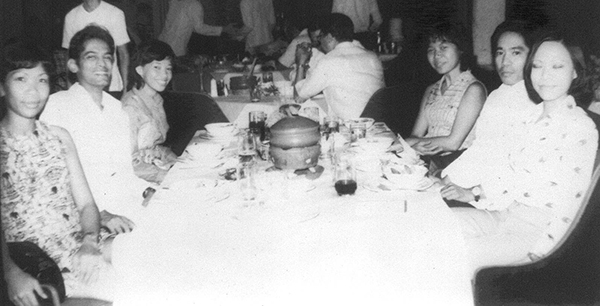

That's them on the upper left side of the photo. This is their only picture together that I have, possibly taken in 1975, the only year they spent together. Then, Mommy would've been 33 and Dad, 29.

Mommy's caption: "Philippine dinner was held to honor Christine Ho, girl to the left of Conrado de Lara, our accountant. To his right is your Tita Terry, across me, then your dad with a naughty smile, and to his right is Carmen Espino Santos."

They met in late 1974 in Manila, while working for International Research Associates, an American-owned market research firm. Dad had come over after a four-year stint working in market research in the United States, and it was the wish of his father—my grandfather—that he get acquainted with the industry in Southeast Asia. All this was to prepare him to assume leadership at the Bureau of Commercial Statistics and Intelligence, a market research company my grandfather founded in Bombay.

For most people, life with their parents can be long-running films, and that's the case between me and Mommy. With Dad, however, it's mostly snapshots, interspersed with a short video clip here and there. If the story jumps back and forth across three decades, it's because the photos are few and far between, and each of them carries volumes.

My story with them starts here; if the smiles on their faces hint that they're up to something, it's because they were, and that it was a secret.

It was in 2008 that I traveled to Bangalore expressly to meet and get to know my dad. There, he told me many things: how he's not Hindu, but subscribes to an Indian version of the Anglican Church; how he was married but by choice and not by arrangement; how he had gotten an annulment and married again; how I have a half-brother and a stepsister; how the memory of my Malayalee ancestors continue to live in houses and inherited property all over Kerala.

To relate everything Dad told me would require a book. To be fair, I would also tie it into my Bicolano roots in Donsol, to find the unintended parallels between the coconut and chili that infuse both cuisines, the differences and similarities between working-class Manileños and upper-class Malayalees, not to mention the family histories that will require the endurance of a teleserye to relate, occasionally breaking into a Bollywood dance.

No, this is not about India, but the prologue in Manila, told with the few pictures Dad showed me on my first trip to Bangalore.

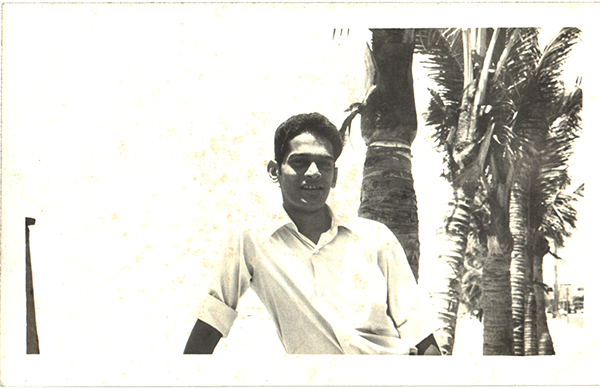

This is Dad crossing Roxas Boulevard. Mommy is positive that that's the Excelsior Building behind him—the mezzanine, to be exact. There, they trained the field people in interviewing. They would go door to door and ask a set of survey questions relating to which client INRA was doing research for. Dad refers to the mezzanine floor as Mommy's HQ, where she kept the field mice in ship-shape (his words). To the right was Casa Marcos, where the first photo was taken; it was also where they'd take clients to lunch or dinner, according to my mom. To Dad's left was the flat he shared with Gil, one of the office executives.

At least one storm lashed Manila during this time. Once, while walking to the office in the high wind, Dad found himself picked up and pressed against a Volkswagen parked by the sidewalk. The Excelsior's guards had to rush out and drag the poor bumbay into the lobby before the wind swept him further away.

Dad also claims that the most comfortable and stylish pair of shoes he'd ever owned was made in a shop on Roxas Boulevard. He just walked in, and the cobbler took measurements and made a mold. Dad wore those shoes for years. Those bell-bottoms he's wearing were also probably made in Manila. There was a tailor who'd visit the office every payday. During these visits, he'd take measurements, collect installments on orders, show fabric swatches.

"Gil and I [liked] to keep up with the times," Dad said, and his threads showed it.

Case in point, he's wearing one of the barongs he had made here. That's his handwriting on the board behind him. Mommy says that beside him are Rene Valencia, a key punch and card sorter operator, meaning he worked with punch cards to process data on the IBM computers they used back then. (I grew up seeing those punch cards all over the house, not knowing what they were for.) The woman with them is Lilian Neri, who assigned staff to manually calculate the percentages necessary to make statistical tables.

Those were analog days, with computations done by paper and pencil. Mommy got her chemical engineering degree using logarithmic tables and slide rules. There were very few computers in Manila then, and there were times they'd rent the San Miguel Corporation's computer to process data during off hours. This meant they'd have to spend a night or two at the SMC office while the computer crunched the numbers.

For this particular picture, Mommy said, "Your dad was assigned to coordinate this data processing stage, then present them to us upstairs for final assembly. The research project at this particular time was Horizon East, a Six Asian City survey among heavy travelers by air. Your dad had some international magazines like Time and Reader's Digest as riders in this study."

Prestigious as it sounds, there were some instances where the situation made data collection, well, problematic. Dad told me a few times about the soda wars, how both Coca-Cola and Pepsi had baranggays under their influence, such that only one company got to sell its products in the sari-sari stores there, and the rival would be barred entry. There were even incidents where the baranggays would smash the rival's bottles and dispose of them. There were also times when the sales numbers didn't match the dispatch numbers. It was soon discovered that the dispatchers had been, well, induced to load full bottles only on the outer layers of the delivery trucks, leaving it with a solid core of basyo—empties.

This is not to say that these cola companies knowingly encouraged this kind of sabotage. It is just as likely the initiative of some complicit individuals in the companies and the baranggays working around a set of restrictions. Such workarounds were common then, in the mid-70s. If INRA had to grease a few handshakes along the way, my parents haven't said anything, or perhaps they won't. Personally, I find it hard to believe that they would, unless somehow coerced into it.

There's a huge chance this is also on Roxas Boulevard, judging from the still-open sky and the coconut trees. While Dad's hometown in Kumarakom, Kerala also has its coconuts, I'd still like to think this was in Manila, near the Excelsior Building.

Because Dad was here from 1974 to '75, he managed to catch Thrilla in Manila on TV. On October 1, 1975, the office suspended all work, set up the largest TV they could find on the main office floor, stocked an ice box full of ice and Pale Pilsen, and sat back to enjoy the fight. Dad also caught a press conference with the fighters and got a photograph signed by Muhammad Ali himself. But don't take my word for it; a cousin of his borrowed it, and no one has seen it since. Apparently, Indians have their version of arboring.

I can't help but think of that time as sun-drenched, idyllic days, disregarding the inconveniences of data gathering and the slowness of number-crunching. They were young, younger than I am now, and still had the future ahead of them. But the future was about to happen to them.

A month after the fight, Dad would return to Bombay to take up his post at his father's company, not knowing that I was already taking shape. He would find out from his flatmate Gil, who would tell him when Mommy was five months pregnant; Mr. Atienza would become one of my godfathers. The following year, my grandfather would pass away, and Dad would marry for the first time.

My Tita Terry, sitting across Mommy in the first picture, would tell me in 2005 that Mommy had spent her nine months carrying me with her and her family. My lolo and lola and Mommy's sisters did not see her pregnant. Mommy wrote once that that was one of the happiest times of her life, when she was finally doing something for herself. Her womb must've been flush with market data, her secrecy, and her bliss. She would give birth to me and bring me home, like one would a foundling with a mysterious father. I have to confess, it's hard to resist these mythic themes, this anemoia.

In 2008, Dad and I were walking home during a blackout in Bangalore, with the traffic crushing and rushing all around us, much like Manila traffic on Manila roads, but with more honking in the darkness. Dad had one more story.

"Two weeks before I was supposed to leave, Mommy slipped me a note while we were in our office. She wrote, 'I heard you're leaving soon. I'd like to spend some time with you.' And that, my son, was when you were conceived." It's a strange thing to hear while auto-rickshaws and motorcycles are rattling past, lights zooming in and away, the city's cacophony carrying on like nothing had happened. I don't know if I would've asked for that story, but there it is.

Dad left for Bombay on November 6, 1975. We would meet for the first time on November 7, 2008, thirty-three years and a day later. My sense of fact will say that this is pattern recognition, that I am ignoring details that don't fit the picture in my head, that there are stories yet untold and undiscovered. But from time to time, something happens that spirals back into the past to dredge up someone's memory—a photograph, an object, an association—and rushes up to join the inexorable spiral into the future.